In the lockdown summer of 2020, I started to rewrite the housing lectures that I had given to students in Paisley with the aim of making a book on Scottish housing. I never finished this because that Autumn I moved to France and to new work with the Kurdish Freedom Movement, leaving behind my library and my free time. Some of the planned book chapters covered subjects I have published on before, and others needed more – and more recent -information, but the section looking at the morphology of Scottish towns was almost complete, and it seems a pity not to put in the small amount of extra work needed to make it fit to share. As an architect, I have always enjoyed not just looking at buildings but also reading them, so as to understand why they are the way they are. I hope that this account can help others enjoy reading the streets around them.

Homes are the main building blocks of our towns and cities. They affect people’s relationship to the elements, and the private lives within their walls – and they also affect community interaction. How homes are combined together is rarely treated with the seriousness that it deserves, but it is this that creates the possibilities or limitations for what Jan Gehl describes as ‘life between buildings, with huge implications for quality of life in general.

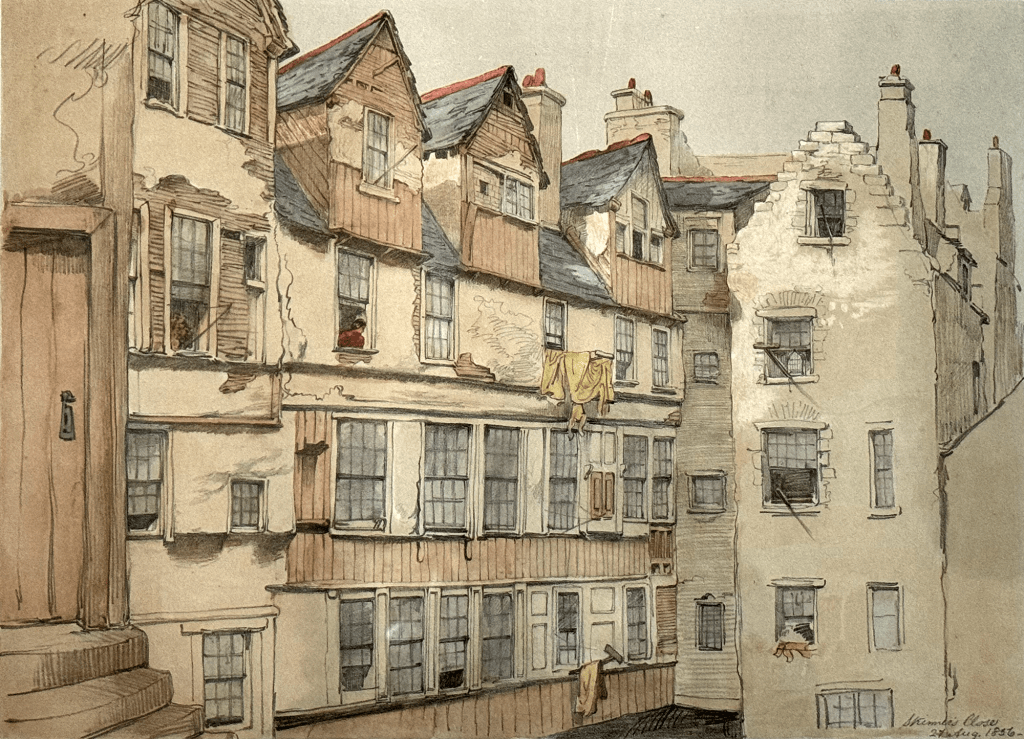

The traditional Scottish town was planned like a fish bone, with tightly packed narrow plots to maximise the number of buildings within the burgh boundary and give as many as possible a frontage onto the main street. The tight space encouraged people to build upwards over many storeys, as well as backwards along the plot. This pattern is still clear in many old high streets, including those in St Andrews, Edinburgh and Elgin .

Most buildings were tenements, with different homes accessed off a common stair. 16th Century tenements often had timber galleries jutting from the upper floors, and the space below might serve as a shop. Grander 17th Century tenements, such as Gladstone’s Land on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, might have a stone arcade to shelter the shop customers. Towns accommodated a wide range of activities, and travel distances were short, but buildings were often overcrowded, insanitary, and dark.

In the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries, as towns expanded beyond their old walls, developers laid out their plots according to the fashionable classical forms of squares and crescents and straight gridded streets, led by Edinburgh’s New Town.

Streets might be constructed piecemeal, but buildings complied to an overall grand design. And, as in much of continental Europe, but not in England where development took the form of terraced houses, most of the homes, except the very grandest, were tenement flats. These included well apportioned apartments, as well as basic homes for the working class. Meanwhile, for the poorest, older buildings in the town centres were subdivided as slum housing .

The Scottish tenement

Tenements of various kinds still provide homes for more than a quarter of Scottish urban households, and stone-built tenements form the main fabric of most central areas. The majority of these were built in the second half of the 19th Century and the very beginning of the 20th Century. [The history of this staple of Scottish housing, especially in Glasgow, has been lovingly recorded by Frank Wordsall in The Tenement: A way of Life. A social and architectural history of housing in Glasgow, Edinburgh: Chambers]

Development was usually promoted by the landowner (or feudal superior) who divided his land into lots that were sold or feued (rented for an annual ground rent) a bit at a time. Releasing the land in stages allowed earlier development to boost the selling price of later lots – and this staged development is often visible in small variations between neighbouring buildings. Most tenements were built by speculative builder-developers who arranged loans from investors. They were able to make a good return from their tenants even after paying interest, maintenance, factoring (property management), and insurance. Developers included both small tradesmen and big building firms.

Development could be constrained by rules written into the title deeds by the feudal superior; old burgh laws addressed legal issues around common parts of the buildings; and parliamentary legislation was used to control a whole range of health and safety issues, from the demolition of dangerous buildings and the closing of unfit dwellings, to minimum ceiling heights and the cleaning of common stairs. In an attempt to stop appalling overcrowding, Glasgow’s City Improvement Act of 1866 introduced a ticketing system. Metal discs were fixed to smaller flats to record the volume of space and the number of people it should accommodate, and sanitary inspectors could visit unannounced at any time to try and check these were being complied with. A similar system was used in Paisley, and later in Edinburgh.

Tenement layout evolved with time and varied with geography. Early Glasgow tenements had an open stair at the back reached through a passage, or close. Later, stairs were enclosed in a curved tower, and a further development allowed direct access to the stair from the close without going outside. By the mid-nineteenth century, the standard tenement plan had the stair fully inside the rectangular block. While Glasgow tenements tend to be entered through an open close and have their stair at the back, Edinburgh tenements more often have a door to the street and stairs at the front. Many Dundee tenements are entered off pletties (platforms) running along the back, an arrangement little used – and name almost unknown – elsewhere.

Middle-class tenement flats, or ‘houses’, could have many rooms in a variety of arrangements, but the standard working-class Glasgow tenement had three houses to a landing: a ‘room and kitchen’ at either side, and a one room apartment – a ‘single end’ – in the middle. All the spaces had bed recesses, and the recess in the ‘room’ could be closed off with a cupboard door (until this was deemed too dangerous in 1900). A further hurley bed could be kept below to be dragged, or hurled, out at night. A back court usually contained the communal washhouse (used on a rota basis) and drying area, also ash pits and, in earlier days, a dry closet toilet. A parliamentary act of 1862 stipulated that every house had to be fitted with a properly plumbed sink, but a water closet only had to be fitted ‘wherever practicable’. It wasn’t until 1892 that internal WCs became compulsory, and tenements sprouted WC stacks at the back, accessed off the half landings. Women increasingly took the family washing to the steamie, where you could also get a bath. Otherwise, young children were washed in the sink, while adults and older children had to use a tin bath in the kitchen, which was filled with pails and screened by sheets.

Some streets included shops on the ground floor, and sometimes a pend allowed cart access to factories or workshops in the back court. From the 1850s, the flat facades began to be enlivened by bay windows, and Glasgow underwent a change of character around 1890 when the local yellow sandstone ran out and builders brought in red sandstone from further afield.

With the old centres abandoned to slum housing, city improvement trusts were established and given powers by act of parliament to buy up and clear the very worst areas. Glasgow’s City Improvement Trust was set up in 1866, and Edinburgh’s a year later. Large parts of old Glasgow round the High Street were cleared, as were over a quarter of the homes in Edinburgh’s Old Town,. City authorities also had the power to close houses they deemed uninhabitable. Other clearances were carried out under the 1875 Cross Act, and Scotland’s densely built cities made particular use of demolition powers. The thousands of households that were displaced were generally expected to fend for themselves. Glasgow City Improvement Trust built a few model lodging houses where people could pay nightly for a cubicle, and also some tenements of varied quality, but there was a general expectation that, as the slightly better off moved into new developments, the poorest would move into the homes they had vacated. No records were kept of where people went, but the areas adjacent to Edinburgh’s demolition sites were soon found to be suffering from increasing overcrowding.

While London philanthropists were building low-profit workers’ housing blocks, Edinburgh gained just two groups of these model dwellings. For the city’s skilled workers, there was also the possibility of buying a house in one of the ‘colonies’ built by a building workers’ co-operative that had come together after a dispute and lock-out. These have a distinctive layout with ground floor flats entered from one side of the row and upper level flats from an external staircase on the other side, giving each house its own garden space. Their closely spaced roads are easily spotted on the city map.

English dreams of garden cities

While the towns and cities of the industrial revolution were appallingly congested and heavily polluted, and the majority of the UK’s urban population lived in dreadful conditions, the owners of the industries lived away from the dirt and crowds and dreamt of an idealised rural past. They collected paintings of peasants, and some of them tried to turn their bucolic vision into a practical reality through the creation of ‘model villages’. Here, workers could benefit from open space and greenery, and were expected to develop a healthy body and mind through sports, art, and traditional village activities.

Port Sunlight, on the banks of the Mersey, was established in 1888 by William Hesketh Lever for the workers (and managers) of his new Sunlight Soap factory – which would eventually become Unilever. Housing was built around allotment gardens, and, although interiors were plain, different architects provided a variety of picturesque frontages. Public buildings, set in areas of parkland, included a theatre, a women’s dining hall, and an art gallery, as well as a hospital, school and church. Besides the numerous sports grounds, there was a gym and an open-air swimming pool. Scots could get a sense of the model village at the 1901 International Exhibition in Glasgow, which included copies of two of the cottages. They are still there in Kelvingrove Park.

Lever wanted ‘to socialise and Christianise business relations and get back to that close family brotherhood that existed in the good old days of hand labour.’ He claimed, in paternalistic fashion, that in Port Sunlight he was sharing his firm’s profits, explaining to his workers:

It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation. [Quoted in Philip Sheldrake (2014) The Spiritual City: Theology, Spirituality and the Urban, Chichester; Wiley]

In Bournville, south of Birmingham, established by George Cadbury in 1893 for workers in his chocolate factory, the cottages have their own large gardens in addition to the public green spaces, and village activities included maypole dancing.

Joseph Rowntree’s New Earswick, established north of York in 1902 for Rowntree employees and other workers, had plans drawn up by Raymond Unwin, and Unwin’s business partner, Barry Parker, helped with the cottage designs. Parker and Unwin were to become key figures in the development of housing and planning.

None of these model villages came cheap, though the Earswick houses were unpretentious. They all demonstrate the importance given to the nuclear family, and to self-improvement under a paternalistic umbrella. Sunlight Soap workers who were off work sick, had to leave their boots in the window to prove that they were not playing truant. And Bournville tenants were given Mrs Cadbury’s ‘Rules of Health’, which included advise not to sleep in double beds. Both the chocolate philanthropists, Cadbury and Rowntree, were temperance supporting Quakers, and neither Bournville nor New Earswick have a pub.

The importance of trees and gardens was also recognised in the early housing developments built by London County Council. The Boundary Estate in Shoreditch, started in 1893, and the LCCs housing in Milbank, begun in 1897, both consist of tenements, but with tree-lined streets and a central garden. And, as soon as they were allowed to develop outwith the city boundaries, the LCC built cottage estates. Public transport had made the suburbs accessible and no longer the preserve of the rich. The first cottage estates were regular in plan, but by the time of the First World War the council was experimenting with more picturesque layouts.

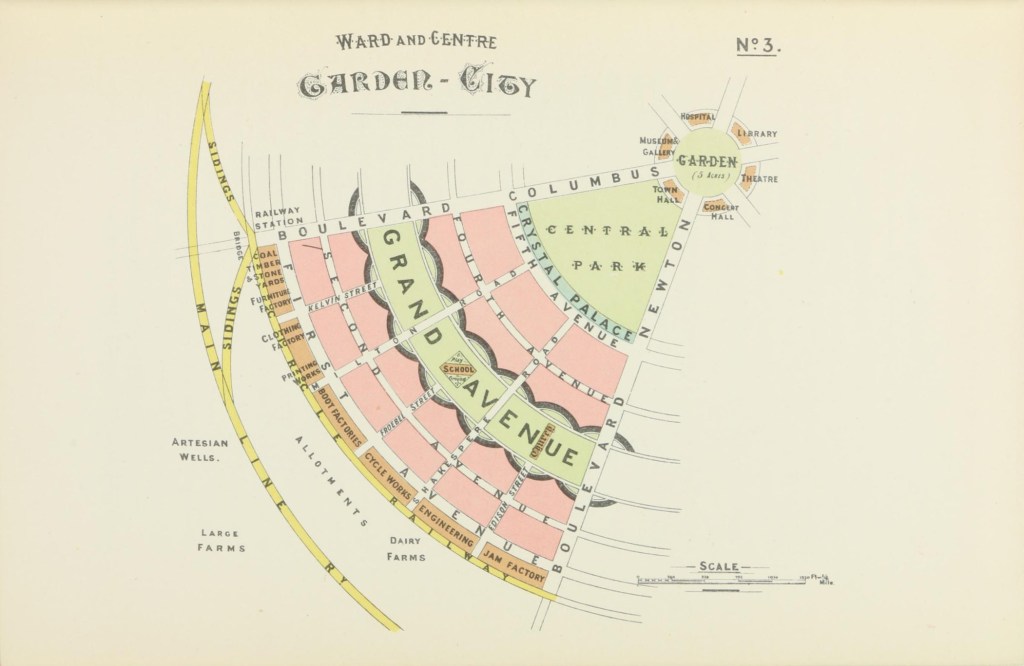

These new approaches to urban living were developed theoretically by Ebenezer Howard in his 1898 book, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. Howard’s job, working for Hansard, kept him abreast of the political debates of the day, and he was inspired by concern for social reform. The year after this publication, he established the Garden City Association, and in 1902 he brought out a new edition of his book under the title Garden Cities of To-morrow.

Radical approaches to the problems thrown up by the industrial revolution had long formed a focus of discussion for socialists. In the early 1870s Engels had called for the abolition of the ‘antithesis between town and country’; and the creation of balanced communities was explored by Kropotkin and by William Morris, whose utopian novel, News from Nowhere, was published in 1890. Howard’s more gradualist ideas chimed with the times, and garnered powerful support. By 1903, First Garden City Limited had been founded to put theory into practice, and had bought land in Hertfordshire for the establishment of Letchworth.

The garden city movement aimed to combine the best of town and country, and to combat both the depopulation of the countryside, and the physical and moral problems of industrial towns. Howard expected to see the development of a lot of small garden cities, accompanied by the contraction of the big cities, including London. He hoped to create a new social order through example, an approach that was doomed to failure for not acknowledging and taking on basic class interests.

In addition, the actual realisation of Letchworth inevitably involved compromise on the original vision. There was no civic centre, and no ring of dispersed clean industries, and Howard’s Henry George-inspired ideas about ground rents ploughed back into the town were only partially realised. Instead of the land being held by a trust, with frequent revaluations so land value rises were captured for the community, the town was run by a joint stock company with standard leases. Letchworth attracted upper-working-class residents, and people looking for an alternative lifestyle, but not people from the lower-working-class. There was nothing disrupting the old relations of society, and in 1915, Letchworth tenants, in common with tenants in many other places, went on rent strike. They appealed to Howard for his support, but he refused to intervene.

For the planning of Letchworth, Howard and his friends turned to Parker and Unwin, who had designed New Earswick, and who, two years further on, would be commissioned to design the much more upmarket Hampstead Garden Suburb. Although the idea of a garden suburb contradicted Howard’s vision of small-scale developments surrounded by rural land, this type of planning was to become very popular.

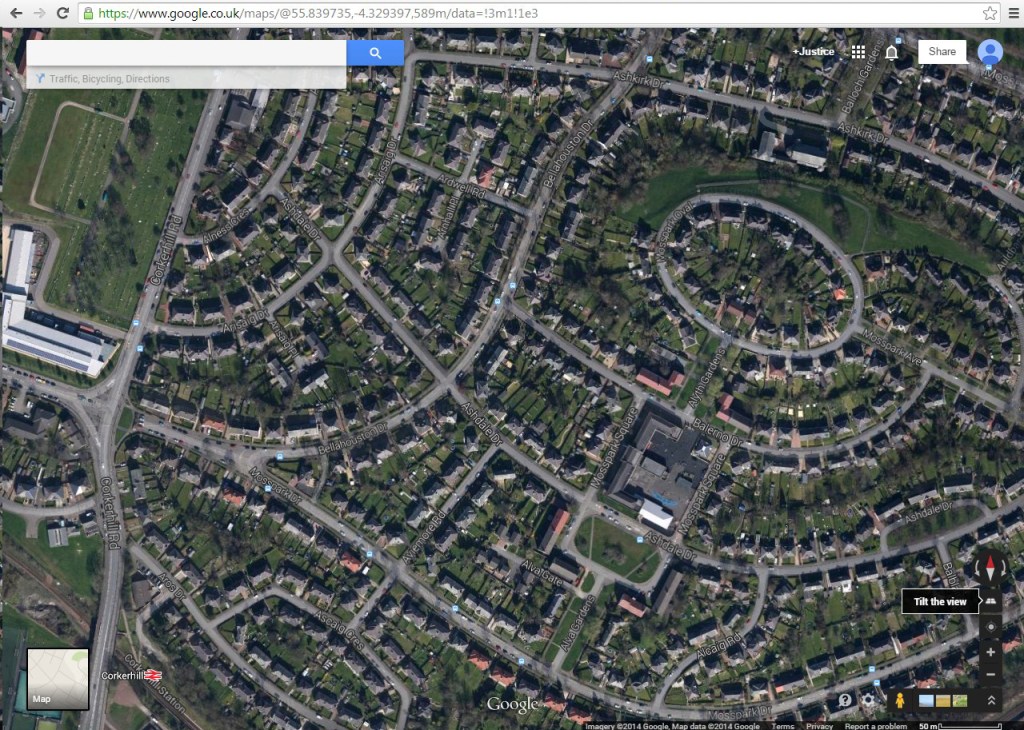

Parker and Unwin’s ideas grew out of the Arts and Crafts tradition, and they aimed to create living spaces that were both practical and beautiful. Their homes were designed to bring in light and fresh air, including through an innovative use of open-plan spaces, though these did not always suit the varied needs of large working-class families. Their urban planning emphasises low densities. It makes a lot of use of circles with radiating roads, as in Howard’s diagrammatic examples, and includes numerous cul de sacs and shared greens between the buildings. Houses are grouped in picturesque clusters, often through the simple technique of advanced and recessed frontages. They have front gardens and hedges, and care is taken to preserve existing trees and to plan with the contours. These ideas were taken up by the emerging town planning profession, and became familiar staples of early twentieth-century development, up until the Second World War.

During the First World War, the UK Government built housing for war workers as ‘garden villages’. Seebohm Rowntree, Joseph’s son, whose investigation into poverty in York had helped inspire his father to create New Earswick, was Director of Welfare for the Ministry of Munitions, and Unwin was their chief housing architect. Among his many duties, he was directly involved with the, relatively plain, housing developments in Gretna and nearby Eastrigg. Plans for a garden city to house workers in Rosyth had begun not long after the announcement of plans for a new naval base there in 1903, but it took the additional pressures of the war to break through Admiralty intransigence and allow construction to begin in the autumn of 1915.

Garden city style planning went on to provide the template for post-war development.

Municipal housing

Councils had already built some housing, but, during the war years, fear of unrest – and of a British version of the Bolshevik Revolution – moved the provision of decent affordable housing to the top of the agenda. The result was the 1919 Addison Act – named after the Minister of Health who introduced it – which brought in government subsidy and made it compulsory for local authorities to assess their housing needs and make plans for the necessary new dwellings.

In 1917, the UK Government had established a committee, chaired by Liberal MP Tudor Walters, to set standards for future house building. Their report, for which Unwin was a key contributor, was completed in 1919, by which time he was the government’s Chief Housing Architect. A manual of his design examples for two-storey three-bedroom cottages was given to local authorities to inform their growing role as house providers. The new houses had front gardens, and back gardens where tenants would be encouraged to grow vegetables, and densities were to be kept at twelve houses per acre in urban areas and eight per acre in rural ones.

The new homes were good quality and relatively expensive, despite subsidies. The first Addison Act housing in Scotland, the Logie Estate in Dundee, even had a district heating system. Many of the new council tenants were lower middle class, and some had servants.

After only a year, council house subsidies were being cut back, and standards reined in. The total floor area for new homes was reduced, and there was less money for paving and fencing – landscaping has always tended to be seen as a luxury in the UK’s public housing. This trend towards greater economy continued until 1936, with houses becoming simpler in outline and combined in longer terraces, and with more use of flatted four-in-the-block arrangements rather than semis. A scheme such as Paisley’s Gallowhill illustrates these changes – and a report in the Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette from 1934 noted that subsidies for Gallowhill homes not completed by 30 June would drop from £9 per house to £3.

Specific slum clearance subsidies, introduced in 1930, were based on the number of homes built, and resulted in homes of less good quality. Blocks of flats built under these subsidies are usually easily distinguished from ‘general needs’ council housing, and the stigmatisation associated with the old slums could be carried through into the new homes.

In England, some big flatted developments took inspiration from Viennese workers flats built by the city’s socialist administration in the twenties and early thirties. Karl Marx Hof, which included kindergartens, playgrounds, maternity clinics, health care offices, libraries and laundries, was the inspiration for Quarry Hill in Leeds (now demolished), but most of the amenities planned for Leeds were never built, and the novel construction system chosen proved a disaster. Scottish pre-war slum clearance housing was not so monumental – more like a modern tenement, though not as cramped as older tenements, inside or out.

Meanwhile, for the growing numbers of owner occupiers, developers were building suburban estates of semis, and lining arterial roads with bungalows.

The forms of interwar housing are clearly depicted in a film produced for Glasgow Corporation in 1922, showing the ongoing development of Moss Park. [Only watchable in the UK, start at 5.19] This pans across a range of house types: semis, four in a block, blocks of flats, and also temporary homes and experiments with different types of construction. Like other developments of this date, the scheme was laid out in a recognisable pattern of spacious circles and crescents. It is not difficult to pick out interwar housing developments on a map.

A new modern world

When society faces major disruption, questions may get raised about the nature of any reconstruction and the possibilities of creating something better than was there before. In the dark days of 1941, long before Britain could be confident of victory, Picture Post devoted an issue of the magazine to ‘A Plan for Britain’, a social and physical prospectus for a ‘new Britain’ that brought together ongoing progressive debate, and which they described as ‘our most positive war aim’. As well as proposals for a health service, pensions, and social security, a section on planning presented readers with an uplifting ‘vision of a new modern world’. Alongside photographs of inspiring examples – a big clover-leaf road junction outside New York, a large flatted development in Leeds, and plans for the reconstruction of Coventry – the article presented before and after images of a typical town to illustrate the possibilities for change through a planned future. The accompanying text listed the problems and the proposed solutions:

Typical section of British land under our present haphazard development:

- Factories and warehouses built on no plan, wherever land was cheap

- The roads are too narrow, too crooked, for modern transport

- The old church survives but it has lost dignity through its unsightly surroundings

- Jerry-built street, no gardens: not enough light and air

- The schools are cramped and dingy, playgrounds are few and badly planned

- The river, once a great traffic artery, flows between out-of-date wharves

The same section reorganised under a coherent plan:

- Factories are grouped away from houses: efficiency as well as health demand it

- The shopping centre and administrative buildings are grouped together

- The roads are straight and wide. A new road for heavy traffic circles the town

- The church, in its garden setting, regains the dignity it had five centuries ago

- Courts and alleys are swept away. New flats stand in a park

- Schools and health centres are spacious and set in the open air

- The river is reclaimed, its banks beautified with trees and promenades

It is an alluring vision, and helps explain so much of post-war planning – even if the benefits of hindsight may make us question almost every ‘improvement’.

Just as the government after the first world war looked to better housing as a ‘bulwark to Bolshevism’, so the Welfare State was seen as the answer to those who might be lured by Soviet Communism. The Beveridge Report was completed in 1942, and also that year, a Committee was set up, chaired by Lord Dudley, to draw up new standards for post-war housing. The Dudley Committee published its report in May 1944, after extensive discussion and surveys, including with women’s organisations. This made recommendations for both internal house plans and the layout of whole estates. The three main room layouts comprised a suggested rural arrangement, with a kitchen cum living room and separate scullery, and two urban alternatives, one with a kitchen cum dining room, a living room, and a utility room, and the other with a ‘working kitchen’ and a living room with a dining recess.

Although the surveys showed a strong preference for detached houses, the committee also looked at other considerations and international practice. They wanted to avoid suburban sprawl and monotonous streets of socially isolating identical homes far from jobs and services. Instead, they call for the creation of ‘neighbourhoods’, consisting of a mix of house types, including flats and maisonettes, to accommodate a community of households of different sizes and ages. As well as homes, each neighbourhood was to include schools, shops, a community centre and plenty of open space.

The idea of the neighbourhood unit had its origins in the garden city movement, but it had returned to the UK via the United States. Clarence Perry, in 1920s New York, called for neighbourhoods of a size to support a primary school, with main roads at the edges and smaller internal roads that were only for local traffic. The Dudley Report’s neighbourhoods were expected to house 5-10,000 people. They were to be constructed in the destroyed city centres, in expansions of small towns, and to make completely new towns. There was no mention of high flats, but the earlier County of London Plan noted that ‘a certain number of high blocks up to ten storeys might prove popular, in particular for single people and childless couples’. [Quoted in Boughton, John (2018) Municipal Dreams: The rise and fall of council housing, London and NY: Verso, p95] These were a recognised part of the modern architect’s palette, along with the slab blocks included in the Picture Post vision.

Immediate housing needs were partially relieved by the use of prefabs, some of which are still providing homes, generally under a casing of new insulated cladding. And the shortage of building materials, together with the legacy of wartime mass production, prompted experiments with factory-produced sections as well as the importation of wooden kit houses from Scandinavia. Traditionally built Council houses constructed immediately after the war retained older forms, but with slightly art-deco details. However, all this was soon to change.

The 1945 Planning Report for Glasgow, drawn up by the City Engineer, Robert Bruce, adopted a fundamentalist modernist vision. The whole of the central core, including the City Chambers and the School of Art, was to be swept away and replaced by an array of towers and slabs. Slum housing was to make way for commercial buildings, with the people rehoused in new developments on the edges of the city, and the report included the first proposal of the inner ring road that still isolates the city centre. Similar processes were happening in other towns and cities, if often to a lesser extent.

The Clyde Valley Plan of the following year, by Patrick Abercrombie and Robert Matthews, took a different approach, proposing instead to reduce overcrowding by dispersing people to purpose built New Towns. Abercrombie had been responsible for the County of London Plan of 1943 (with the council’s own architect) and for the Greater London Plan of 1944. These recognised the value of many old buildings and of local communities, but not of the built fabric of working-class areas, such as Stepney, which they wanted to rebuild on healthy rational lines. Abercrombie’s London was linked to the surroundings by wide arterial roads, complete with flyover junctions, leading to an inner ring road. Outward expansion was restricted by a green belt – an idea long discussed but, up to then, never properly implemented, with further growth pushed out into New Towns, as he later proposed for Glasgow.

For the Glasgow councillors, New Towns had the disadvantage of taking away a large proportion of their population, while Bruce’s wholesale demolition would have been prohibitively expensive. In the end they decided on a compromise solution including a combination of New Towns, peripheral schemes (Castlemilk, Easterhouse, Drumchapel, and Pollock) and comprehensive redevelopment areas.

The rebuilding of the central area was still being proposed in 1949, when Glasgow Corporation (the City Council) constructed a model of their plans and made a short explanatory film, Glasgow Today and Tomorrow. As well as the modernistic city centre, the film describes (in clipped English) the new road system designed for motor traffic, and new spacious community areas with amenities – not just houses. (It also includes footage of an overcrowded single end to show what they wanted to replace.) Pathé footage of the model includes brill-creamed assistants making the final touches, as well as bemused Glaswegians.

New Towns and green belts were a further development of garden city ideas. Although they were designed as self-contained places, the houses were generally built before the associated amenities, forcing the new residents to rely on a domestic existence. The first post-war New Town was Stevenage, begun in 1946. The Scottish New Towns, built to accommodate Glasgow’s ‘overspill’, are East Kilbride, started in 1947, Glenrothes, Cumbernauld, Livingstone and Irvine. Despite all the idealism about building communities, neighbourhood centres in the various new schemes were often poorly designed and inadequate.

The driving force of much of post-war planning was the motor car. Even when actual car ownership was low, car travel was seen as the future. One way of accommodating this was the segregation of motor traffic and pedestrians. A seminal model for achieving segregation was imported from the States, the land of the motorcar.

Radburn planning is named after Radburn in New Jersey, which began construction in 1929 as a Town for the Motor Age, though the Great Depression prevented its completion. Radburn’s houses back onto a series of cul de sacs which provide vehicular access. A completely separate footpath system in front of the houses links to a central park and includes underpasses to cross the main roads.

The first UK Radburn development was begun in 1950. The Ministry of Housing’s 1953 manual included a suggested layout, and versions of the plan were popular in the 1960s and 70s. Less satisfactory aspects included confusion over what was the front and what the back, lack of privacy in the gardens, safety concerns for the isolated footpaths, and grim garage courts.

Cumbernauld New Town was fêted for its completely separate footpath and road systems. A 1970 promotional film for Cumbernauld Development Corporation described it as a ‘brilliantly logical solution to the conflict of cars and people’. Cars can link quickly to the intercity motorway system (we watch a young man pick up his girlfriend and drive off in his MG almost without stopping), but back gardens are linked to pedestrian routes, and everywhere can be reached on foot within 20 minutes without crossing a road. The much-derided concrete central complex (now scheduled for staged demolition) housed all the town’s amenities and also its office-based businesses. Despite the easy pedestrian access, it had parking for 5000 cars. In 1967, the Institute of American Architects voted Cumbernauld the world’s best New Town, observing that it had ‘great significance for… the future development of community architecture in the Western World’.

Like most of Scotland’s public housing developments, Cumbernauld combined low-rise housing and tower blocks. Multi-storey housing blocks – high flats if you’re in Glasgow, multis if you’re in Dundee – are the ultimate symbol of modern architecture. As conceived by Le Corbusier, and illustrated in his utopian Ville Radieuse plan of 1924, these should be point blocks in landscaped surroundings, conceived to maximise sun, space and greenery. As built in the UK, they often lacked space as well as basic amenities. Even in more open layouts, the surrounding grass, trees and basic paving could rarely be described as landscaped. But politicians and planners loved modernity. This was the period of Harold Wilsons much-quoted embrace of the ‘white heat’ of the scientific ‘revolution’.

The language of modern architecture created geometric compositions that combined horizontal forms with towers, and slabs, sometimes raised off the ground on concrete ‘piloti’. These varied forms could be related to the recommendations for varied house types, though designs became increasingly weighted in favour of high-rise flats. Access decks and bridges between blocks – first used in Sheffield’s Park Hill in 1957 – kept pedestrians away from the cars below, and saved on the number of lifts.

Promotion of high flats was official policy. In 1956 the government brought in an increased subsidy for high buildings to reflect the greater building costs, and from 1963 they pushed industrial building methods. System-built flats were especially popular for slum clearance schemes, though they never achieved the claimed efficiency.

Many of these flats suffered from design faults and bad workmanship, and this was not helped by the adoption of relatively untested building systems – nor, it may be surmised, by some prominent examples of corruption. Tenants suffered damp and mould and high heating costs – especially after the 1973 oil crisis. Poor sound insulation left them exposed to noise from all sides, and there were frequent problems from broken lifts. High flats were blamed for increasing people’s isolation, and were difficult for families with young children. Playing in the corridors disturbed all the neighbours, playing outside was too far away for mothers to supervise, and, as it says in the song, ‘ye cannae fling pieces oot a twenty-story flat’. (A jeely piece is a jam sandwich.) Although there was very little criticism when the towers were built, there were already well-recorded concerns about high-rise living before the 1968 gas explosion in Ronan Point. After a corner of this new twenty-two story London block collapsed like a pack of cards, killing four and injuring seventeen, the tide began to turn against high flats.

However, in 1971, Glasgow Corporation was still looking forward to a modernist 1980, and commissioned a film to portray this vision. Major old buildings were now appreciated, but we see old tenements and corner shops being pulled down to be replaced by spacious and clean new housing areas, complete with shopping precincts (traffic free but constructed with parking) and supermarkets. The film praises the flats designed by Basil Spence in the Gorbals – the first comprehensive development area – that would soon, in the mid Seventies, see a rent strike against appalling damp, and that were eventually demolished in 1993 after a failed refurbishment in the late 80s. After panning over the Red Road flats, the final shots, accompanied by dramatic music, follow a saloon car round the curves and flyovers of the nearly empty new road system. This was meant to be the first of two films but the second one was abandoned before it was completed.

In most of these developments, the buildings sit like sculptural objects in the middle of public space that is often windy and underused. In the 1970s and 80s concerns grew that this open planning was encouraging crime and vandalism. Oscar Newman’s more nuanced theories about ‘defensible space’, published in 1972, which called for spaces to be clearly perceived as belonging to and surveyed by adjacent homes, were developed by Alice Coleman into an uncritical architectural determinism that neglected social issues. In Utopia on Trial, published in 1985, she argued that public spaces should be divided up and assigned to individual owners. Her work chimed with Thatcherite individualism and was very influential, leading to theories about designing out crime.

The 1980s also saw an increasing move against Radburn planning, which could produce worryingly quiet pathways or isolated garage courts, and a move towards spaces shared by vehicles and people, which were busier and better supervised. These were made safe for pedestrians by slowing cars with various traffic calming formations – chicanes, road narrowing, tight turning radii, humps, and textured surfaces. However, planners still demanded large numbers of parking spaces per home.

By this time, councils were no longer building big schemes. New social housing developments – council and housing association – were only small-scale infills; and these were often built to a more traditional high-density street pattern. Much more housing was being built by private developers who wanted to meet the recognised standard market for homes with private car spaces or garages.

Improving the tenements

Despite all the ambitious plans for rebuilding, pre 1914 tenements continued to provide homes for a large part of the urban population, as they still do today. Over the decades, they had become more and more run down, with only minimal repairs and no upgrading of facilities. And back courts had become even more neglected after their railings were removed as part of the misguided attempt to provide steel for the war effort. (Cast iron was of no use.) While appreciation had grown for grander Victorian buildings, the tenements were inextricably linked in official minds with the poverty and overcrowding of their tenants and the dangerous neglect of their landlord owners.

In the 1950s and 60s, Glasgow Corporation attempted to get rid of the problem by designating twenty-nine Comprehensive Development Areas where almost everything would be demolished and rebuilt. Between 1955 and 1965, 32,000 homes fell to the wreckers’ ball, but by the mid-sixties, dissatisfaction with the new schemes was growing. At the same time, the building of the replacement housing was taking longer than planned, and homelessness was a growing worry. The result was a new interest in the possibilities of refurbishment, and housing associations started to use government grants to improve tenement flats to house the homeless

In a bid to improve housing standards, the 1969 Housing (Scotland) Act required Local Authorities to ensure that all houses that fell below a set Tolerable Standard were closed, and demolished or improved; and required them to designate Housing Treatment Areas. Glasgow Corporation set up a new House Improvement and Clearance Section of the Town Clerk’s office, with a programme that included a lot of demolition, but also improvements for 10,000 tenement homes.

By now, many tenants had bought their homes off their landlords, for whom they had become a poor investment, and most tenements were in multiple ownership. The Corporation’s improvement system used Compulsory Purchase Orders to buy everyone out and empty the buildings. These were then done up to the new standards and let as council housing.

In Annie’s Loo, Raymond Young describes how, in Govan, local people worked with the Corporation to establish an alternative method, helping people to stay in and improve their own flats through public participation backed up by a pioneering community housing association.

Govan Comprehensive Development Area was launched in 1968, and the New Govan Society was set up by local people – including church leaders and councillors – that same year. This was a time when local authorities were being urged to work more closely with the people they served, and the Society became a formal partner of the council. The University of Strathclyde Architecture Department was also involved, initially through Young’s student project.

After surveys and discussions it was agreed that the partners would carry out short-life improvements in an area that was scheduled for redevelopment in 15 years’ time, and that the work would focus on installing bathrooms, as the majority of flats still had only shared loos, and no baths.

In 1971, the society set up the first community housing association – Central Govan Housing Association – as a not for profit, community-run landlord. Membership was open to everyone living in the area. The housing association, the residents’ association, the architectural team and the corporation all worked together. The corporation found alternative homes for people who wanted to leave. The housing association bought out flats from landlords who wanted to sell and from owners who couldn’t afford the improvements, and those former owners became housing association tenants. As flats became empty, it became possible for the single ends to be combined with neighbouring flats, whose owners bought them out. And residents were able to stay in place while the work was done. The improvements were coordinated on site by the architectural team, using sets of standard plans. Prices were negotiated with the builders, and residents got help with costs from government grants and bank loans. The first bathroom, built in a former bed recess – ‘Annies’ loo’ – was shown on STV and received 300 visitors.

The process was a huge success. Plans became long term, and the next thing to be improved was the back courts. The tenements are still providing good homes.

The process that was developed in Govan was taken up in other places, and the 1974 Housing Act allowed more generous grant funding. Most later schemes did require the residents to decant, though the aim was still to rehouse them in the same building. And most people became housing association tenants. In 1974, Glasgow Corporation made a film to demonstrate how tenements could be improved.

Housing associations grew into a major force for carrying out inner city improvements, and the model used for taking over private housing was later adapted for taking over rundown council housing in Castlemilk and Easterhouse. But, over recent decades, the associations have become more divorced from local communities. Housing Association Grants have been reduced, and the associations have been forced to rely on more private borrowing and become more market driven. Many former housing association tenement flats were bought under the Right to Buy; and some of the tenements now need a further round of major refurbishment, especially if they are to meet new energy standards.

Market forces

In recent years, most development has been speculative housing driven by market forces, and planning rules created in an environment where cars were king, still dictate layouts with much of the open space dominated by parking. New housing includes blocks of tiny cramped urban flats, and middle-class suburban houses set in their own patch of garden ground with garage and driveway.

Flats and student housing are built to attract investing landlords. We have seen a massive reduction in social housing, both through change of tenure via the Right to Buy, and through large-scale demolitions of many of the housing schemes described above. Some social housing has been upgraded to meet new standards, often with new insulating cladding, and some has been protected by cameras and secure entries, or, more humanly, by concierges. New social housing developments have been limited in size, but they have provided an opportunity for more innovative design, especially for greater energy efficiency. Social housing not only has to meet higher space standards than commercial developments, but it is also not restricted by the developers’ short termism.

Looking to the future

The social significance of different spacial arrangements was highlighted by Jan Gehl, the Danish Architect and Urban Designer, in his book Life Between Buildings: Using public space. This was published in Danish in 1971, but many of his ideas are only now making their way into the mainstream.

Gehl calls for a built environment conducive to outdoor activities that facilitate social interaction and strengthen community. A good physical framework can promote more and longer outdoor activities; and, while an empty space may stay empty, a busy space encourages more activity. He wrote,

The major function of the communal spaces is to provide the arena for life between buildings, the daily unplanned activities – pedestrian traffic, short stays, play, and simple social activities from which additional communal life can develop, as desired by the residents.[Gehl, Jan (2011) Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, Washington DC: Island Press, p. 57]

The functionalism of much twentieth-century planning considered physiological needs – light, air, sun, access to open space – but omitted psychological and social considerations. The reliance on the car, the desert planning of big housing schemes, and private houses castle-like in their private gardens, all mitigate against walking and casual contact.

Gehl’s solution is a hierarchical system of communal spaces: private, semi-private, semi-public, public. When houses are grouped around semi-public space, that space is seen to ‘belong’ to those houses – to be, in Newman’s terminology, defensible space. Gehl’s prescription is an approach to planning that facilitates use of public transport, cycling and walking, that ensures activities are not too widely spaced out, and that encourages short walks where people meet each other. He calls for cars to be left at the edge of residential areas so that people have to walk the last 50 to 150 metres, and for paths constructed on desire lines with minimum changes of level, but with twists and variety to reduce perceived distance.

Gehl provides a palette of components for creating people-friendly neighbourhoods. Narrow frontages and irregular facades provide visual stimulation and variety. Streets and squares are kept to human dimensions. There is an easy relationship between private and public space, such as can be achieved by small front gardens that encourage interaction across the fence. There are pretexts for going out and meeting others, such as small front gardens to work in, and play areas for children. Public spaces are visible from private homes. There are plenty of sitting places for people to linger – including benches for the elderly and those who need frequent rests, and informal sitting places such as plinths and steps. And, of course, those external spaces need to be designed to give protection from the wind and to maximise sunshine and greenery. As Gehl observes, spaces surrounded by dense low-level buildings provide a much better microclimate than open spaces around isolated blocks.

These ideas have tended to be much better taken up in the Nordic countries than in the UK, with the 1970s redevelopment of Byker in Newcastle the noteworthy exception that proves the rule. Ralph Erskine, the architect of New Byker, based his practice in Sweden. The Byker plan demonstrates a hierarchy of space, with housing grouped around semi-public areas with clearly defined entrances. Balconies and small gardens link private and public, and there are numerous public seating areas with benches at right angles to encourage conversation and tables to encourage activity. While the history of Byker has not been easy, that has been due to poverty and deprivation rather than planning.

Although the middle classes have rediscovered the value of traditional town and city centres, with their dense planning and local facilities, and there has been a nostalgia for the urbanism of traditional streets and squares, it is only very recently that the dominance of the car has begun to be questioned. Pollution, congestion, and above all, climate change, are ensuring the widespread take-up of the concept of the 20-minute neighbourhood, where most daily needs, including some jobs, are within 20 minutes travel distance by foot, bicycle or public transport. (This is a concept that has come under extraordinary attack from conspiracy theorists – no doubt backed by the car lobby – who have misrepresented it as a restriction on movement comparable to a ghetto.) Edinburgh’s new design standards allow no parking space for new homes in the centre and a maximum of three spaces for every four homes elsewhere..

Besides the tensions created by the economics of a market-driven system and the conservatism of the volume house builders, ideals of community can come into tension with pressures for privatised safety. But for most of us who experienced the safe isolation of the coronavirus lockdown, the importance of the casual meeting with neighbours has become only too apparent.